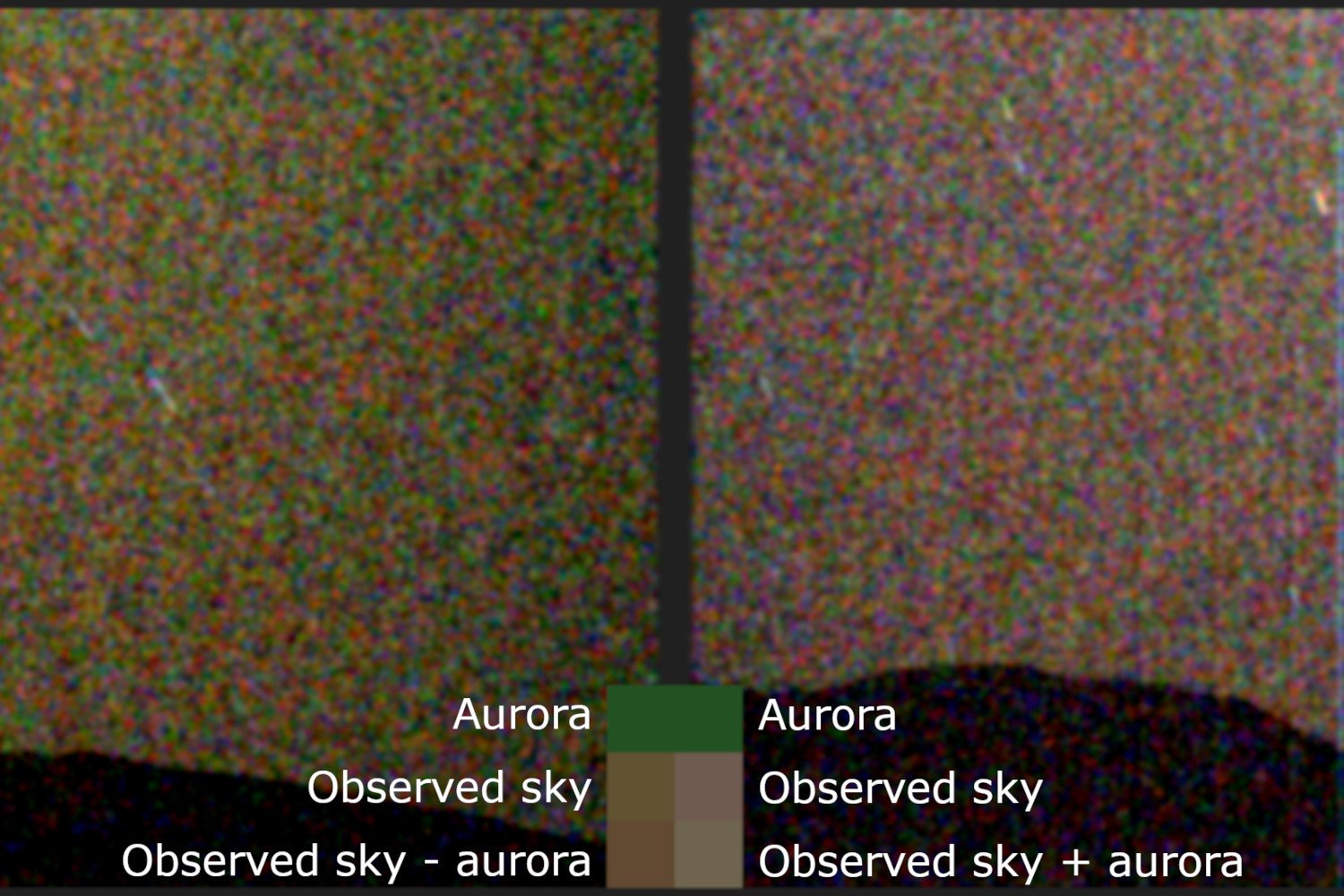

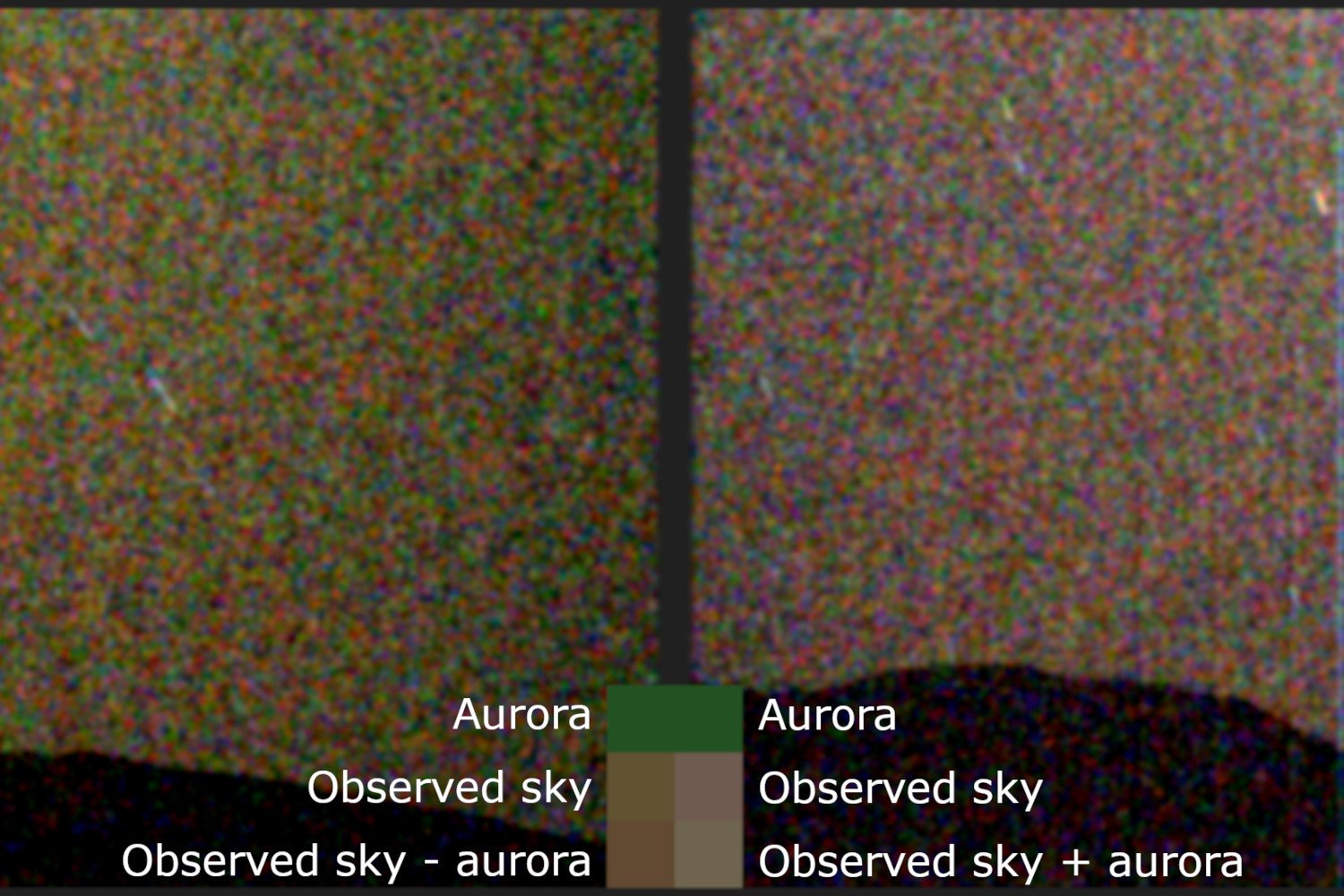

Scientists used cameras aboard NASA’s Perseverance rover to capture unprecedented views of the Red Planet’s green glowing sky.

Former SpaceX employee Douglas Altshuler is taking aim at the Musk-owned company in a new federal discrimination lawsuit.

The 58-year-old Washington resident and his lawyers filed the lawsuit last month. The suit alleges that Altshuler’s employers threatened to fire him for taking frequent bathroom breaks, even after he told them that he had Crohn’s disease. Altshuler also alleges that he was exposed to chemicals, was often denied meal breaks, and was denied proper overtime pay during his 18-month employment there.

According to the lawsuit, first obtained by The Independent last week, Altshuler was hired to handle customer support calls at SpaceX’s Redmond, Washington, facility in June 2023. He appeared to have no issues with the job until early 2024, when his direct supervisor “began tracking Mr. Altshuler’s bathroom breaks and repeatedly criticized [him] for using the bathroom,” the lawsuit claims. Altshuler reportedly provided his supervisor with a doctor’s letter explaining that he has Crohn’s disease, a form of chronic inflammatory bowel disease that often forces people to use the bathroom frequently, particularly during active flare-ups.

Altshuler claims that he asked and was given assurance by two supervisors for a reasonable accommodation to use the bathroom as needed. But soon enough, his direct supervisor allegedly began to needle him again over his toilet habits, tracking his bathroom breaks and writing him up whenever he was away from his desk for more than 10 minutes. Altshuler says he then pleaded his case to higher-ups at SpaceX, which reportedly led to retaliation from his supervisor during his next performance review; the lawsuit claims that the supervisor “alleged performance deficiencies which were never brought to [Altshuler’s] attention before.”

Though Altshuler was assigned to a new supervisor in October 2024, his issues reportedly continued. Altshuler alleges that he was potentially exposed to chemicals in November from “industrial parts being dried in the kitchen oven where employees cook their food.” He reported the incident to the Occupational Safety and Health Administration and filed a worker’s compensation claim over it as well. Afterward, he claims that he was further retaliated against, with his new supervisor reportedly threatening to fire him for using the bathroom “too often.” In early January, Altshuler was allegedly told by Human Resources at SpaceX that his “concerns of retaliation were unsubstantiated.” Soon after, on January 9, 2025, he was fired, reportedly for “alleged deficient performance.”

This isn’t the first time that former employees at SpaceX have alleged mistreatment and retaliation from the company’s management. In January 2024, the National Labor Relations Board accused SpaceX of illegally firing eight employees after they began to circulate a letter in 2022 calling for SpaceX to distance itself from Elon Musk’s behavior and comments at the time, which included allegedly sexually harassing employees at the company. These employees have since filed their own lawsuit in California State Court against Musk. Musk has also fired employees at X, formerly Twitter, since taking over ownership of the social media company.

In speaking with The Independent, Altshuler’s lawyers argue that his firing is a clear-cut case of discrimination against him for his disability, as well as an example of retaliation against him for trying to speak up about it. Altshuler has further claimed that he was often required to skip his meal breaks and work long hours without added pay. “The company’s actions are egregious and in clear violation of the law. Mr. Altshuler intends to seek all legal remedies that are available to him,” Clive Pontusson, a former trial attorney for the U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, told The Independent.

Gizmodo reached out to SpaceX for comment regarding the lawsuit but did not hear back by the time of publication.