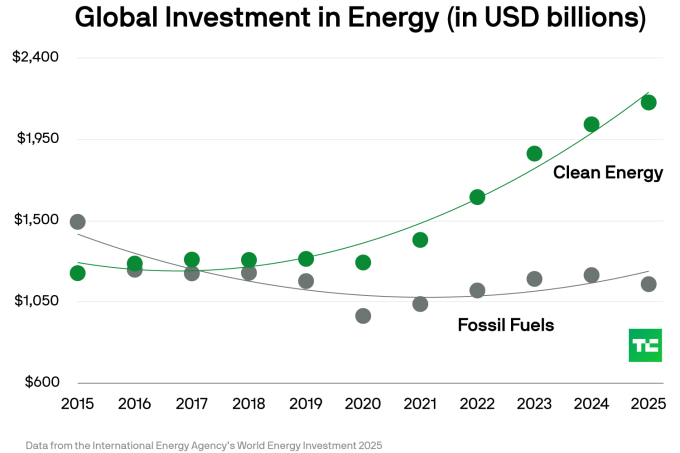

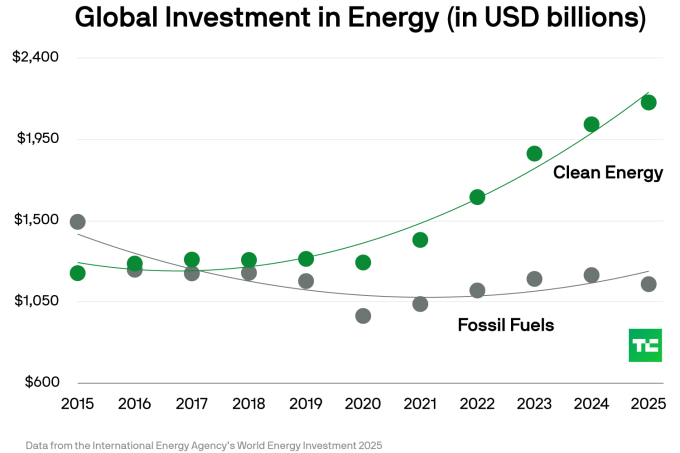

The world is set to invest nearly twice as much in clean energy as fossil fuels this year, according to a new International Energy Agency report.

While fossil fuel outlays are still significant — about $1.15 trillion this year — they’ll be dwarfed by clean energy, which is expected to receive $2.15 trillion in 2025.

But the real takeaway is that the energy transition doesn’t show signs of slowing.

Plotting the two investment trends is revealing. Over the last decade, fossil fuel investment has been relatively steady, if declining slightly. There has been an uptick since a drop that coincided with the pandemic, but even that shows signs of softening this year.

But clean energy investment follows a different path, a far more aggressively positive trend: The curve is up and to the right.

For data nerds: A second-order polynomial fit to the fossil fuel investment does a reasonable job of explaining the variance (R2 = 0.74), suggesting the world might be extracting a bit more oil, coal, and gas in the near future. But the same type of equation applied to clean energy figures fits the data far better (R2 = 0.94). Unless the world takes a U-turn — something that hasn’t happened in the 10 years the IEA has collected this data, pandemic included — expect bigger clean energy numbers next year.

The big question is whether it’ll be too little, too late.

To hit net zero by 2050, the world has to invest an average of $4.5 trillion annually, according to a report from the World Economic Foundation. That’s double this year’s investment, which sounds like a lot. But analysts have previously issued overly cautious clean energy investment forecasts. The trend in the new IEA data suggests that the goal is within reach.

Clean energy’s exponential growth won’t last forever; the trend is likely to taper off in the coming years, just like it did in the mid-2010s. But as I’ve written before, these sorts of fits and starts are not unusual, and adoption of new technologies is never continuous. Instead, it’s influenced by global economic trends and the learning curve that companies face when incorporating them into their businesses.

Ultimately, by 2050, I suspect average annual investment will probably meet or exceed the $4.5 trillion annual rate that the World Economic Forum calls for. Clean energy technologies are cheaper by the year, which makes them more accessible. Indeed, 85% of electricity demand growth in the next two years is going to come from developing and emerging economies, and while cheap coal has driven the narrative in many of those, solar and wind shouldn’t be counted out.

The wildcard, of course, is data centers. In the U.S., at least, utilities are confronting demand forecasts with enormous error bars. Those forecasts may fall short, but utilities tend to err on the side of caution, which means finding more power.

Some will turn to gas turbines, others will bet on nuclear. But in the next few years — and likely over the long term — renewables paired with energy storage will have the upper hand. They’re probable winners not just because they’re getting cheaper, but because they’re modular. They can be deployed at a range of scales and prices. It’s easy for them to be everywhere, and that’s something investors love to see.

Keep reading the article on Tech Crunch